Source Descriptions

Cobbett's Parliamentary History of England, 1066-1803

Cobbett's Parliamentary History of England, From the Norman Conquest in 1066 to the Year 1803, From Which Last-Mentioned Epoch it is Continued Downward in the Work Entitled "Cobbett's Parliamentary Debates" 1625

The Parliamentary History of England From the Earliest Period To the Year 1803, From Which Last-mentioned Epoch It is Continued Downward in the Work Entitled "Hansard's Parliamentary Debates

- Author: William Cobbett (1763-1835), assisted by J. Wright

- Publisher: Thomas Curson Hansard (1776-1833); William Benbow (1784-?1841)

- Number of Published Volumes: 36

- Number of Records: 6,542

"The origin or first institution of parliament lies far hidden in the dark ages of antiquity, that the tracing of it out is equally difficult and uncertain. The word parliament is comparatively of modern date, derived from the French, parler, and signifying the place where they met and spoke, or conferred together. It was first applied to general assemblies of the states, under Lewis VII in France, about the middle of the 12th century; but it is certain, that long before the introduction of the Norman language into England, all matters of importance were debated and settled in the great councils of the realm; a practice which seems to have been universal among the northern nation, particularly the Germans, and carried by them into all the countries of Europe, which they over-ran at the dissolution of the Roman empire. In England this general council hath been held immemorially, under the several names of mieliel synoth, or 'great council'"*

"In 1106, says Matthew Paris, Henry I called together the great men of the realm, by his royal mandate, to meet at London where he first softened and sweetened them separately, by honied words and expressions; and then, having met together, he made a speech to them."*

It was illegal to publish the proceedings of the Parliament.

"On the 13th of April 1738, the House of Commons, after a Debate which will be found at p. 800, came to the following Resolution: "That is an high indignity to, and a notorious breach of the Privilege of, this House, for any News-Writer in Letters or other Papers (as Minutes, or under any other denomination) or for any printer or publisher of any printed Newspaper of any denomination, to presume to insert in the said Letters or Papers, or to give therein any Account of the Debates, of other Proceedings of this House, or any Committee thereof, as well during the recess, as the sitting of Parliament, and that this House will proceed with the utmost severity against such offenders."**

"So the compilers of periodical publications adopted a covert method of giving the Debates. The Gentleman's Magazine published the "Debates in the Senate of Lilliput" and the London Magazine gave a "Journal of the Proceedings and Debates in the Political Club."** These and other periodicals gave print space to the debates without incurring the notice of the Houses of Parliament.

Each of the 36 volumes contains the following Table of Contents:

- Proceedings and Debates in Both Houses of Parliament

- Articles of Impeachment

- Queen's Speeches

- Queen's Messages

- Lists of the Members of Both Houses

- Petitions

- Protests

- Reports

- Representations

- Persons Filling the Several High offices of the State, During the Reign of Queen Anne

- Contents of the Appendix

- Index of the Names of the Several Speakers in both Houses of Parliament

We have digitized section one: the Proceedings and Debates in both Houses of Parliament with these examples:

| DATE | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1702 May 4 | Declaration of War against France and Spain | 16 |

| 1740 Feb 1 | Debate in the Commons on the Navy Estimates | 404 |

| 1786 May 22 | Earl Stanhope's Plan for Rendering the Reduction of the National Debt Permanent | 17 |

| 1802 May 13 | Debate in the House of Lords on the Definitive Treaty of Peace | 689 |

| 1803 Mar 8 | King's Message Respecting Military Preparations in the Ports of France and Holland | 1162 |

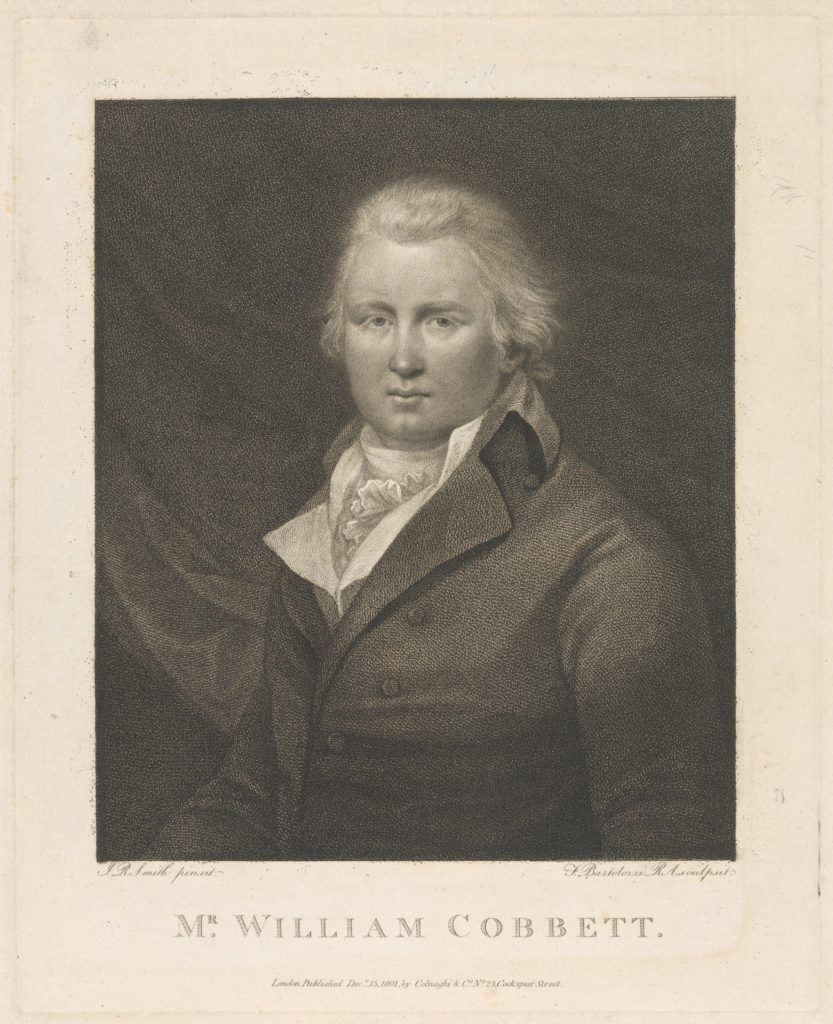

William Cobbett, a noted radical and publisher, began publishing Parliamentary Debates as a supplement to his Political Register in 1802, eventually extending his reach back with the Parliamentary History. Cobbett's reports were printed by Thomas Curson Hansard from 1809. In 1812, with his business suffering, Cobbett sold the Debates to Hansard. From 1829, the name Hansard appeared on the title page of each issue. Neither Cobbett nor Hansard ever employed anyone to take down notes of the debates. So, for this reason early editions of Cobbett's are not to be absolutely relied upon as a guide to everything discussed in Parliament.**

William (no middle name) Cobbett was born on March 9, 1763 in Farnham, Surrey and was taught to read and write by his father who was a farmer and publican. At twenty, he went to London and served as a clerk in Gray's Inn for nine months, at which time he joined the regiment and was stationed in Nova Scotia. He used the spare time to educate himself, particularly in English grammar. While in New Brunswick, he gathered information on some corrupt officers and wrote The Soldier's Friend (1792) protesting against the low pay and harsh treatment of enlisted men. Fearing indictment, he went to Philadelphia in 1793 and became a controversial political writer and pamphleteer, writing from a pro-British stance under the pseudonym Peter Porcupine, in The Porcupine, published 1800-1801. Immediately, he started his Political Register questioning the policies of the Pitt government. His strong voice for parliamentary reform landed him in prison for "treasonous libel" and he was sentenced to two years in Newgate. On his release, a dinner in London, attended by over 600 people, was presided over by Francis Burdett, who shared Cobbett's view on parliament. He continued his voice in the Political Register and incurred the wrath of the government again. Suspecting he was going to be arrested for his "seditious writings" he fled to the United States. For two years (1817-1819), he lived on a farm in Long Island where he wrote Grammar of the English Language and with the help of William Benbow, continued to publish the Political Register.

When Thomas Paine died in 1809, Cobbett planned to take his remains for a proper burial on his native soil, but his remains were still in Cobbett's possession when he died in 1835 over twenty years later.

He continued to publish controversial material and in July 1831 was charged again with seditious libel for writing a pamphlet entitled Rural War. He conducted his own defence and was so successful that the jury failed to convict him. He tried several times to be elected to the House of Commons but was unable to achieve that wish. In his later life, his faculties were impaired and he developed paranoia to the point of insanity. From 1831 to his death in 1835, he farmed a few miles from his birthplace in Farnham, where he is buried. His sons were trained as solicitors and founded a law firm in Manchester, still called Cobbet's in his honour.**

*Preface to Volume I

**Wikipedia

***Preface to Volume 10

Note: Cobbett published many treatises, books, pamphlets and articles. In addition to his Parliamentary Debates he wrote The American Gardener (1821), which was one of the earliest books on horticulture published in the United States. In 1829, he wrote The English Gardener, which has been compared with other important books on gardening. He is best known for his book in 1830, Rural Rides, written as he rode around the country making observations on what was happening in the towns and villages, and which is still in print today.

mh:March 2013